by Kylie Reed, PhD, Post-doctoral fellow Duke University and University of North Carolina

No matter who we are or where we come from, there’s one thing we all do: go to the bathroom. On average, humans spend around 10 to 15 hours a month relieving ourselves of liquid or solid waste (aka, peeing or pooping). About 2.5 to 5 of those hours each month are specifically dedicated to pooping, although this comes with a lot of differences in how often it happens, how long it lasts, and the total amount of time it takes each day. Though we don’t always talk about it, most of us pay some attention to what comes out of our bodies. From the Bristol Stool Scale to age-old phrases like “taking the Browns to the Super Bowl” to being toilet-shy at the office, poop (and its variety of smells, shapes, and sizes) is something we all are familiar with. But have you ever thought about what information might be hiding in the toilet? Scientists do, and there’s a lot we can learn from poop.

Digestion starts in your mouth when you chew food, and it continues through your stomach and intestines. In an ideal situation, your body absorbs nutrients and energy in the small intestine, passes the rest to your gut bacteria (i.e., the community of trillions of microorganisms residing in the digestive tract) in the large intestine, and then what’s left exits as stool. But, like most things, the digestive system isn’t perfect. Sometimes, things like stomach bugs or stress-related issues disrupt it. In reality, our complex, efficient digestive system can easily be upset by countless disturbances in ordinary life. Even in healthy people, about 10% of carbohydrates aren’t absorbed, and malnutrition or certain illnesses can make digestion even worse (Keller & Layer, 2014). If someone doesn’t eat enough for a long time, their gut can weaken, slowing digestion and causing other problems like dehydration (Kelly, 2021).

These imperfections highlight why the calorie count on a food package doesn’t always match what your body gets from the food. For example, the calories in your 100-calorie snack pack of pretzels may not all be absorbed by your body. Digestion varies from person to person, and your gut microbes also play a big role in how much energy you digest, produce, or utilize from food (Jumpertz et al., 2011).

For people with eating disorders like anorexia nervosa (AN), digestion can be even more complicated. During treatment, people with anorexia nervosa often need to eat a lot of calories to gain weight, but their bodies don’t always absorb those calories effectively. This is partly because their digestive system has been affected by starvation. On top of that, reintroducing food after starvation can cause uncomfortable digestive symptoms like bloating or constipation. This led us to ask how our imperfect digestive systems may impact individuals with AN. Does the starvation linked to AN damage the gut? Does this damage make it harder to regain weight during treatment? And could improving gut health help with recovery from AN?

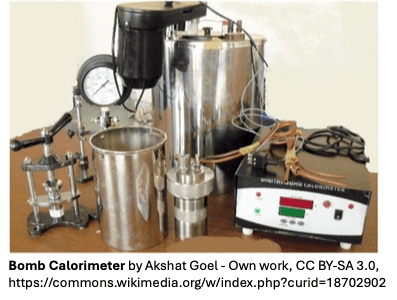

To explore these questions, we used a method called bomb calorimetry, which measures how much energy is left in stool. This allows us to see if what goes in really comes out. For example, if someone eats 2,000 calories but their stool contains only 200 calories, it means their body absorbed 1,800 of the calories they ate. However, if they eat 2,000 calories and their stool contains 1,800, then their body only absorbed 200! We analyzed over 300 stool samples from healthy people and people with AN, both before and after treatment. We found that people with AN lose more energy in their stool at the start of inpatient treatment compared to healthy individuals (Reed, Bulik‑Sullivan, et al., 2024). However, after eating calorie-rich foods during treatment, their stool had less energy, indicating that digestion and absorption likely improved. This suggests that poor digestion in AN is not permanent—it can get better with proper nutrition. So maybe “what goes in” and “what comes out” are not fixed amounts of energy from food but instead exciting, dynamic numbers that can be affected by our overall health, our gut health, what specific types of food we eat, and more.

These findings made us think about how we approach treatment. Could adding in therapies right away that target gut recovery help patients recover faster? Could we reduce the uncomfortable GI symptoms that often come with renourishment? Focusing on the gut might help people with AN gain weight more efficiently and comfortably and lower the risk of relapse after treatment. GI dysfunction is often at the center of eating disorders but is easily overlooked when other medical and/or psychiatric parts of the illness take over. While treating the gut won’t cure eating disorders by itself, it could be an important part of a holistic plan to help people recover. There is no question that recovery from all eating disorders is an uphill battle. If we could at least take the edge off of the GI symptoms, we could help make it more tolerable and efficient.

We know there are many aspects of AN that we cannot change, like genetics or past experiences. However, research shows that we can help the body recover a healthy gut environment quickly (Dubrovsky & Dunn, 2018). For example, scientists have found that we can rapidly change the gut microbiome (David et al., 2014) through lifestyle choices, diet, and medications. This means that the gut and its microbes could play a powerful role in supporting individuals with AN and their doctors during treatment.

While microbiome-based therapies for AN are not yet available, the future looks promising. In the last 20 years, the cost of sequencing the microbiome (analyzing the genes of all those tiny organisms in the gut) has dropped dramatically—from $10,000–$50,000 per sample to as low as $200–$500 today. This 96% decrease in cost between 2013 and 2023 (Cost of NGS | Comparisons and budget guidance, n.d.) makes it easier than ever for scientists to study the gut microbiome. As conversations about eating disorders treatment expand worldwide, experts across fields are now ready to work together to push this science forward—combining gut health therapies with traditional medical and psychological care—in hopes of making life better for people with eating disorders and their families.

For a fun video on how we process stool samples, click here.

REFERENCES